Commercially produced “dog food” is the norm today, but was it always so? How did our ancient ancestors feed their canine companions? Ever wonder why dog kibble comes in cereal boxes? Why are those biscuits called Milk Bones? Discover all of this in more in “What you didn’t know about the history of dog food.”

Our long history with dogs

Dogs have lived alongside humankind since our earliest days on earth. According to researchers, there is evidence going as far back in time as 15,000 years. Dogs buried in ancient cemeteries with their human families are found all around the world including in Skateholm, Sweden, the Iberian Peninsula, and Danger Cave, Utah. The 4,000 year old dog remains from Iberia were analyzed by researchers who determined that they lived on a diet similar to that of their human companions: grains like wheat, vegetables, and animal protein. This trend of sharing the family meals with dogs continued largely unchanged for thousands of years.

Ancient dog meals

One of the first written accounts of a dog’s recommended diet is in Roman Marcus Terentius Varro’s book Res Rustica, Farm Topics. Says Varro, “The food of dogs is more like that of man than that of sheep: they eat scraps of meat and bones, not grass and leaves … You should also feed them barley bread, but not without soaking it in milk … They are also fed on bone soup and even broken bones as well … Their habit is to eat during the day when they are out with the flocks, and at evening when these are folded.” Written in 37 BCE, the book goes into great detail on the care of many animals domesticated at the time. In the part about dog care he also recommends a paste of filberts to be rubbed on the ears and between the toes to prevent flystrike, and he quotes the proverb, “canis caninam non est: dog doesn’t eat dog.”

Similar recipes can be found in varying records over the generations, with writers advising canine diets made up of some combination of bread, milk, and meats less palatable to people like bones, organs, and fat. Unless dog owners were well to do, these meals were typically made up of leftovers. In 1844 Frenchman Nicholas Boyard wrote that dogs should be fed what is left at “the bottom of the stew pot.”

Literary references and common sense will tell us that, for many generations, dog owners fed their dogs whatever was available and not needed for human consumption. Dogs likely supplemented their diet, as many still do today, by hunting and scavenging. It wasn’t until 1860 that “dog food” became a product all its own.

Dog biscuits

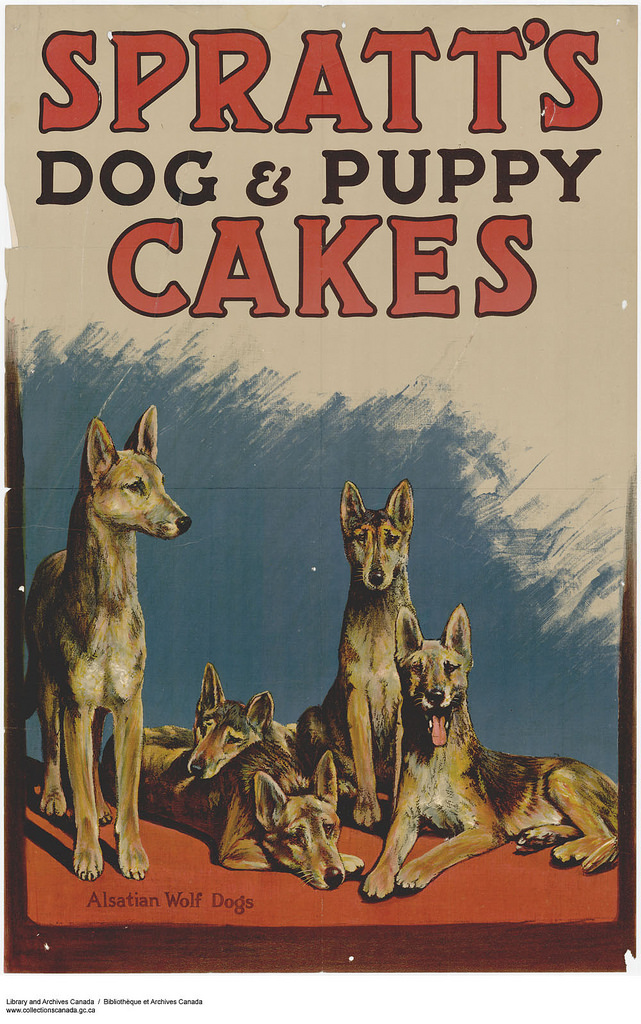

Ohio electrician James Spratt was in London plying his trade and, apparently, seeking other business opportunities when he noticed sailors tossing some of their “hard tack” biscuits to eager dogs begging on the docks. After returning home, he started a company producing a dry, long shelf life product similar to the sailor’s biscuits but marketed for dogs. He called it the Patented Meat Fibrine Dog Cake, although it consisted mostly of grains and beet root, with the meat source remaining a mystery.

Spratt’s business was successful, targeting higher-income people who could afford such luxuries with claims of both convenience and superior nutrition. He marketed his product through the American Kennel Club, placing an ad on the cover of the January 1889 AKC Journal. He obtained testemonials from members like William J Dunbar, who stated, “My greyhound, Royal Mary, winner at Altcar of last year’s Waterloo Plate, was almost entirely trained for all her last year’s engagements upon them,”

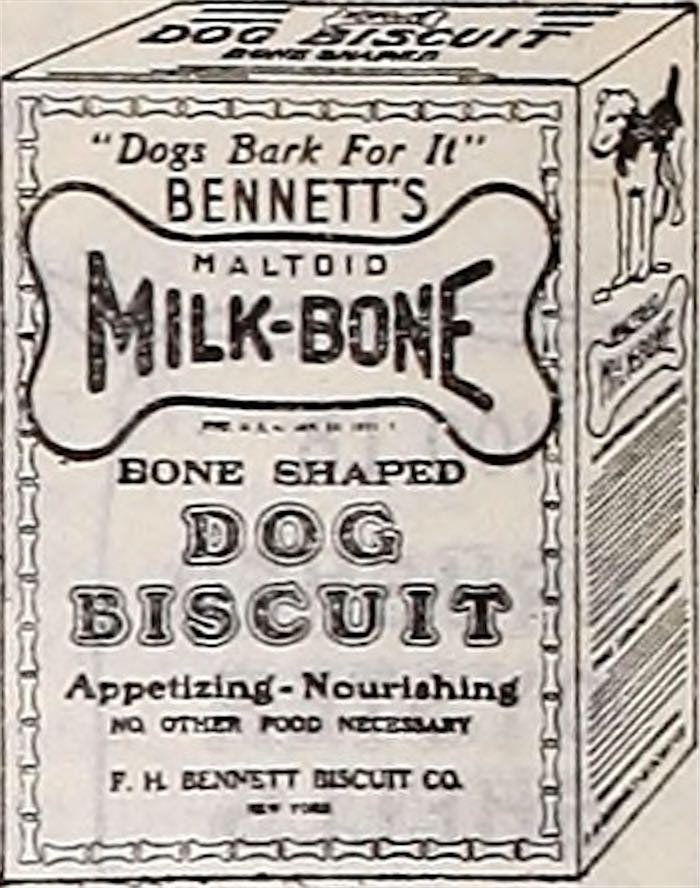

In 1907 American inventor Carleton Ellis, credited with the creation of varnish, paint remover, and margarine, came up with the idea for the now-iconic bone shape for the dog biscuit. In the tradition of feeding dogs waste products, Ellis was working on a recipe for dog biscuits utilizing excess milk from local dairies. According to legend, Ellis created a formula and presented it to his own dog … who refused to eat it. Returning to the drawing board, he decided to try something novel. Rather than changing the recipe of the biscuit, he changed the shape, and his dog then gobbled it up. Whether this really happened or not we’ll never know, but it does make for a good story.

The palatable and visually appealing cookie was a hit, and was soon mass produced by the F.H. Bennett Biscuit Company in the Lower East Side of New York City. In 1931 the company was bought out by the National Biscuit Company aka Nabisco and the product was sold under the name — you guessed it — Milk Bones. Nabisco’s contracts with grocery stores ensured profitable sales and made Milk-Bones a household word, even today.

The Great War and canned dog food

As the world became industrialized and people moved to cities, horses became more plentiful and less valuable. Kept in less than ideal conditions and worked to death in the absence of humane laws, horses became a source of cheap meat for dogs. This practice of feeding dogs horse and other meat not desired by humans was likely common for some time, but after WW1 there was such a glut of unwanted horses that the process became commercialized.

Aspiring New York businessman Phillip Chappel supplied over 100,000 horses for the U.S. military during this time. After the war, the horses were no longer needed so many went straight to the butcher. The book and movie War Horse dramatizes the story of one such horse who survives the war and aftermath, but most were not so lucky. While some cultures eat horse flesh, many do not, so there was not enough of a market to sell all of this meat. In 1922 Chappell found a solution by taking over an old packing plant in Illinois and setting up his dog food canning business. He called the food Ken-L Ration, a play on words of K-Ration, soldier’s food.

The venture was so successful that they soon ran out of a local supply of horses, leading to the decimation of the American Mustang now known to most people thanks to the efforts of activists like Velma Bron Johnson aka Wild Horse Annie. For decades, wild horses, seen as pests by those who grazed their cattle on the same public land, were rounded up and slaughtered en masse. Most of this meat went to the now-booming canned dog food market, and these despicable practices continued until the Wild Free-Roaming Horse and Burro Act was passed in 1971.

Old books

Before the internet, I whiled away many an afternoon sitting cross-legged on the library floor absorbing knowledge from books old and new. The school I attended was so out of date in general that the sanitary napkin dispensers in the women’s restrooms proclaimed, “BELTLESS!” If you don’t get the joke, that’s about as relevant as motel signs saying, “COLOR TV!”

Their library had some real gems from the 40’s including dog, cat, and horse care books complete with black and white photos. I marveled at how different the dogs looked — a subject for another article — as well as the attire of the owners, the different way of speaking and writing, and the feeding guide. These books, usually written by a breeder, would often detail the diet fed to the dogs, which differed little from ancient accounts in its combination of grain, milk, and meat. So although the commercially produced biscuits and canned diets were sold for many years, “dog food” was still not in the mainstream.

Another war

Some people alive today still remember WW2 and is many facets, including rationing and other restrictions. Till the day she died, my grandmother saved bacon fat in a can and folded up every piece of aluminum foil for re-use. She also hoarded sugar and jam packets from restaurants, because who would pass up free food?

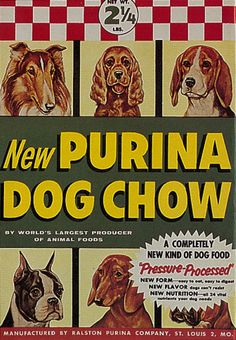

One of the items most needed in war time was metal, so the dog food canning industry took a hit and Ken-L Ration fell out of favor. Enter General Mills and Ralston Purina. Ever wonder why a bag of Dog Chow smells like breakfast cereal? These producers of popular products like Chex and Cheerios found a profitable market for the byproducts of their human-grade food as well as a way to package it without using metal. That’s right, what we now know as kibble was first made from machines used to make breakfast cereal, and it was packaged in the same cardboard boxes, some of which you will still see today on store shelves. By 1956, Dog Chow was one of the leading brands and the first to be made using extrusion.

Superior nutrition?

Extrusion technology took off in the 60’s and 70’s and dry dog food became big business. In 1958 a group of pet food industry lobbyists calling themselves The Pet Food Institute launched a campaign to promote commercial pet food as the only option. As you can see, they were quite successful. Virtually any pet expert today will proscribe against feeding dogs “people food” and would scoff at the home made diets which sustained our canine family members in good health for thousands of years.

Stay tuned for What you didn’t know about the history of cat food